There’s something almost unpleasantly ironic about this collection. The cynic in me would decry it for hiding behind a household name (well, a Whovian household name) while, in many ways, completely sullying it. My forgiving side – the one that grants the benefit of the doubt – would say that it tried to do something different and largely succeeded. But there is a phase shift in evidence here: a gradual erosion, nay, evolution of the straightforward narratives that have been the backbone of the Target range ever since its 1973 inception. We saw it last year, where stories we’d watched and rewatched were worked and reworked at the hands of the people who were novelising them until some were borderline unrecognisable. From one perspective, the liberties taken with Day of the Doctor and Rose were atypical. From another, they were the thin end of the wedge.

But the wedge seems to be fattening, and by the time you get to the end of the fifteen stories that make up this compilation, it’s easy to feel a little jaded. There is a sense of editorial mismanagement: that straightforward stories would not be enough; that it would be better to rewrite, reevaluate and reimagine the Doctor, occasionally removing him from the narrative entirely. Sometimes (Una McCormack’s Grounded, which re-examines an often overlooked footnote in Ninth Doctor history) it works. Other times, it doesn’t. Matthew Waterhouse, for example, turns in The Dark River, in which Nyssa and Adric punt down the Mississippi in the company of an escaped slave, while the Doctor is off doing something else.

This would be fine, except for the love story. Granted, it isn’t quite a love story, more of a yearning look. But it reads like bad fan fiction and it is, I report with great sadness, more of a recurring trait than an anomaly, as if someone high up read through a first draft and then thought “Oh, that’ll do”. Waterhouse isn’t the only actor to feature in the Target book, and Colin Baker’s contribution (Interstitial Insecurity, which takes place at a crucial moment during the Doctor’s trial) fares rather better. Baker may have been short-changed on screen, but you sometimes wonder whether his Doctor might have lasted longer had he been granted the opportunity to contribute to a script.

It’s frustrating. Things start well enough, with Gatecrashers (Joy Wilkinson) plunging the Thirteenth Doctor and her companions into a locked room mystery on a drab, grey planet. Yaz even gets to do a bit of police work, almost. A rushed, mostly expository third act and unsatisfying conclusion leaves it hanging, but it is a decent facsimile of the sort of thing we got in Series 11, for better or worse. It’s followed by Journey Out Of Terror, a companionable First Doctor story hampered by constantly shifting perspectives that do nothing to bring any subtlety to proceedings. Terrance Dicks’ Save Yourself (his first posthumous publication) comes next, with a reasonably entertaining stab at off-screen events during The War Games. It’s not exactly his finest hour, but most of Dicks’ hallmark traits remain intact, right down to the wheezing and groaning.

Still, there’s a sense of fatigue setting in as you work through, even if you leave gaps between your reading sessions. The Time War figures heavily in the book’s second half – from genesis (Mike Tucker’s entertaining The Slyther of Shoreditch) to the eye of the storm (George Mann’s Decoy, in which the War Doctor takes on a Dalek fleet). War costs, we’re reminded with laborious regularity. Ever wanted to know what Umbreen’s secret first husband was writing home before the events of Demons of the Punjab? Ever wondered what was in all those Thijarian dispatches? Ever wanted to read them? Thanks to Vinay Patel, you can. It is a maudlin and drab way to close any book, never mind this one.

Keep the spade to hand and there are occasional treasures buried amongst the ephemera. In Citation Needed (Jacqueline Rayner), we get a narrative recap of hundreds of years of Time Lord history as chronicled by a sentient encyclopaedia – one of those glass bottles the Doctor keeps on his library shelf – and which races down the timeline with the bemusement of Ashildr watching empires rise and fall at the end of The Girl Who Died. Too ambitious in scope to ever be truly successful, at least within the context of its framing device, it is nonetheless chock full of meta-references and in-jokes that tend to work more often than they don’t – Rayner’s description of the events of Heaven Sent had me laughing out loud, as did her entry for Graham, which barely expands upon the words “Always hungry”.

Some of the Classic tales are even better. Matthew Sweet’s The Clean Air Act is not only the collection’s undoubted highlight but also a strong contender for the best Third Doctor story I’ve ever read, anywhere, despite scarcely featuring the Doctor at all. The UNIT family practically jump off the page, buoyed by Sweet’s vivid, elegant prose – “Mr Hesketh was tearing across the lawn of his house towards Sergeant Benton,” he writes, before adding “Seconds later, Benton was flying backwards under the influence of a punch to the face.” It reads like vintage Who, with an eloquent modern slant that Dicks and Letts would almost certainly have adored, and it’s a crying shame that Sweet wasn’t around for the seventies. Just a few short paragraphs after the punch to the face, Yates and Benton are discussing whether a young female protester who goes by the name of Mastersson has anything to hide. “He’s good,” Yates observes, looking at the teenager’s crew cut, “but not that good.”

Then there’s Turning of the Tide. Jenny Colgan’s novella-length love letter to the parallel universe first encountered in Series 2 has had many Amazon reviewers up in arms for what it does to the metacrisis Doctor and Rose, and perhaps some of it is justified. There is so much to talk about it almost deserves its own separate write-up, and perhaps at some point in the future we’ll do an article on this (Phil, can we do an article on this? And can I write it?) but the executive summary is basically a series of bullet points covering pregnancy, unemployment and a serious identity crisis. No longer calling himself the Doctor – at Rose’s behest, we might add – the human doppelganger now known simply as ‘Corin’ finds himself tackling an alien invasion without a TARDIS, sonic screwdriver, and most of his predecessor’s knowledge, or personality.

Ultimately, the problem with Turning of the Tide isn’t that it’s badly written – as narratives go just about all the boxes are ticked – but rather that it crosses a line, taking the show into territory that might be best left unexplored. Perhaps for the first time proper, you realise exactly why the BBC have been reluctant (until now, that is) to follow up on what happened after Rose walked into her Norwegian sunset. It may be uncharted waters but there are sharks – a morose backstory and a flawed, vulnerable Doctor who is frankly very difficult to like are among its many failings. There’s a scene in Superman II where the caped wonder temporarily sheds his powers (for about six minutes) in order to shag Lois Lane: Tide is rather like that, stretched out for 50 pages. It’s not that anything that happens within it is unbelievable; it’s rather that Rayner treads far too close to the likely truth, and the net result is a classic example of what happens when you open Pandora’s box: the Doctor, as it turns out, is no longer in there.

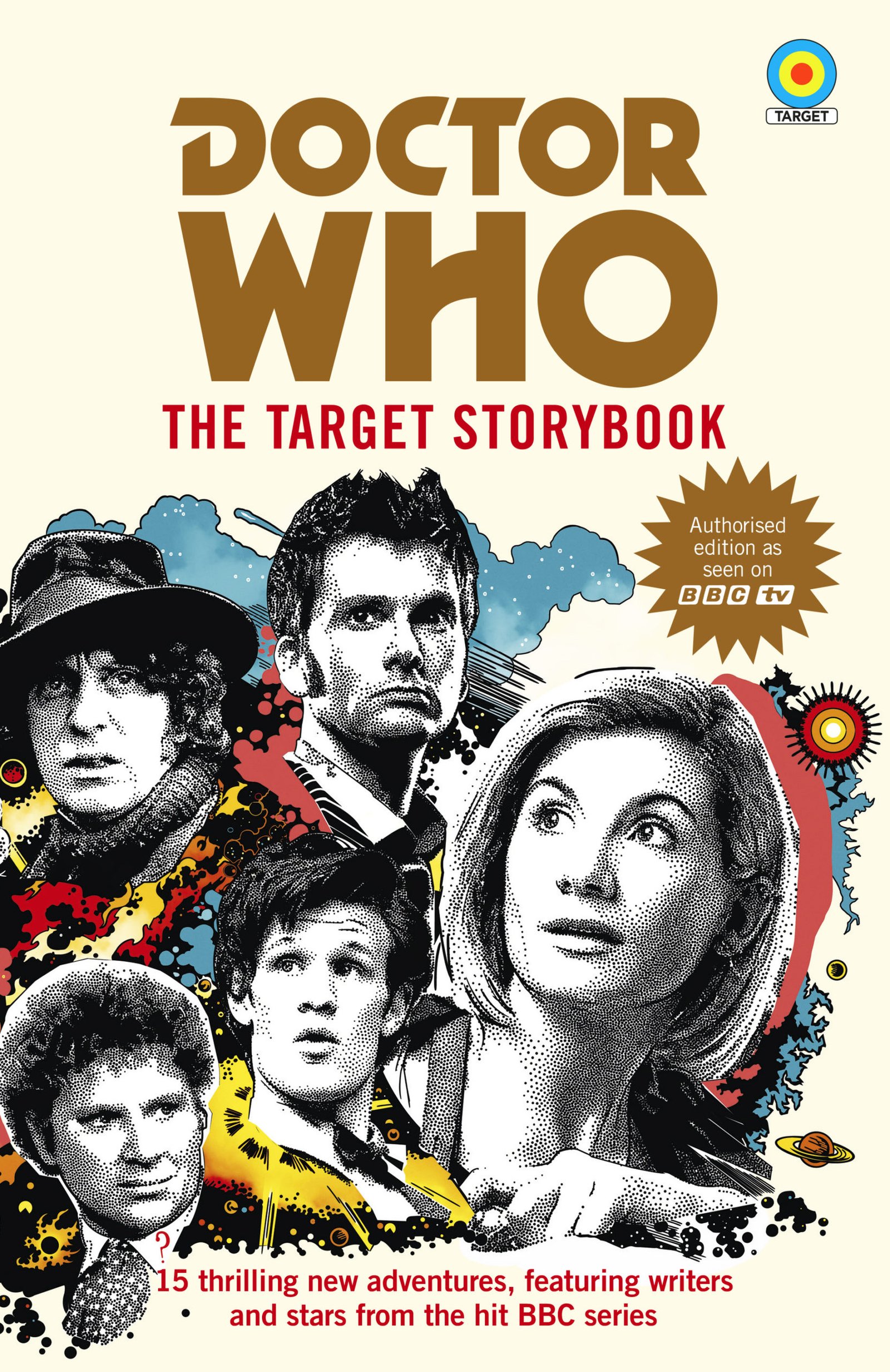

He may have been cancelled, but you can’t help feeling that Gareth Roberts had a rather lucky escape. This is an elegantly packaged volume, clear and easy to read, and graced with sensational artwork by Anthony Dry – authentic to the traditional style, even if the Thirteenth Doctor is given predictable but perhaps undeserved prominence, but this really is one of those times when it is impossible to judge a book by its cover. It looks like a Target book, and there are times, when you scrape away the delusions of grandeur and find yourself at the heart of a good story, when it even feels like one. It’s just a shame that it so often misses its mark.