Ah, The Celestial Toymaker. I’m not old enough to have seen it on its original transmission and, sadly, I have never read the Target novel (have you seen the price that book is now commanding?), but my original exposure with the Toymaker left me with a different interpretation of him, and not the evil entity he is supposed to be.

Let me start from the beginning…

My ‘proper’ introduction to Doctor Who fandom started roughly about the same time as Doctor Who Weekly was released. I was a paper-boy delivering out of a newsagent just off Wandsworth Common. Mr Patel, who owned the shop, introduced me to Doctor Who Weekly #1 as something I might be interested in. Having seen the programme on and off since The Daemons, I was immediately hooked.

I had also been a comics reader all my life and I primarily bought the publication because of the comic strips where I was enticed by Dave Gibbons’ beautiful artwork (the definitive comic strip Fourth Doctor, in my humble opinion).

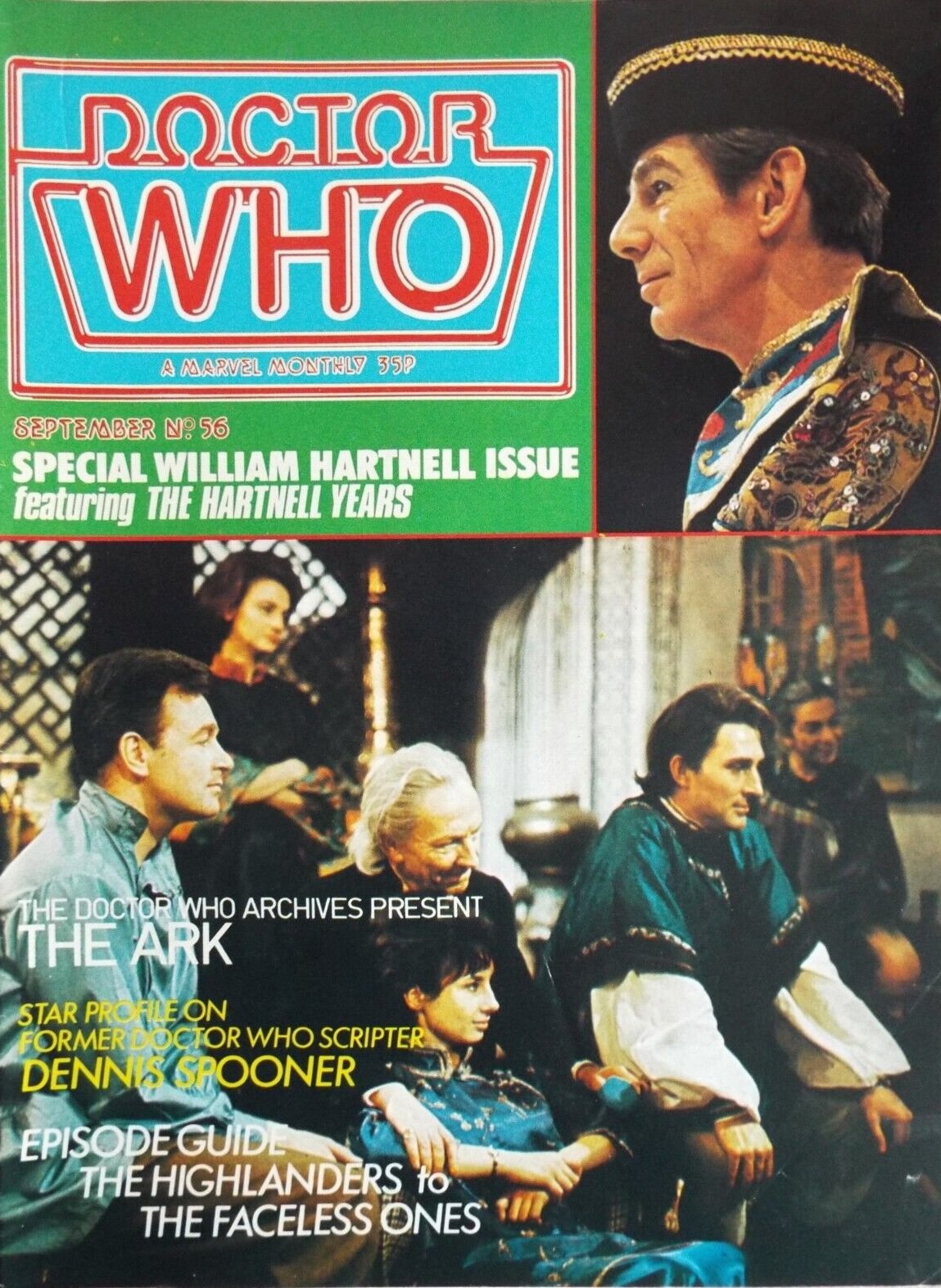

It was a back-up strip that introduced me properly to the Celestial Toymaker in Doctor Who Monthly (no longer weekly) #56: The Greatest Gamble. You see, gravitating towards the comic strips meant that many of the articles of past foes tended to pass me by. I only made a cursory note of the photographs that were used, in previous issues, so I was aware of the Celestial Toymaker, but not who he was.

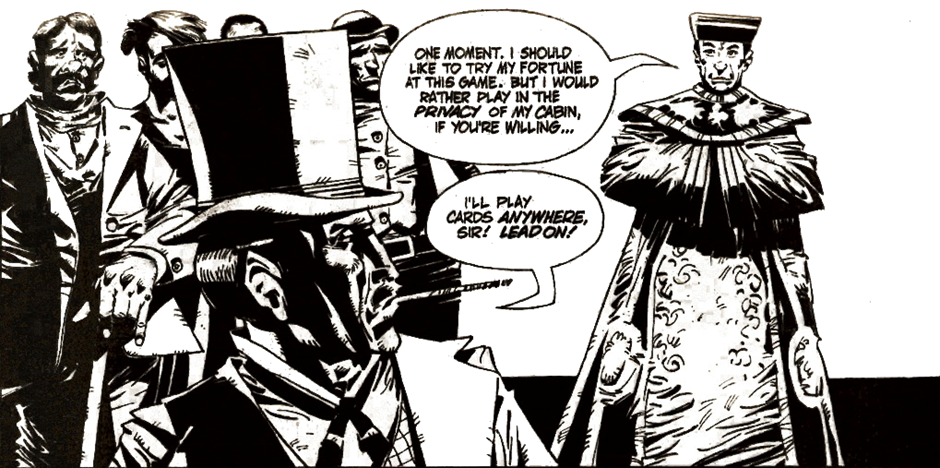

For those not familiar with The Greatest Gamble: a gambler, named Lefevre, is on a Mississippi paddle steamer playing Poker, sometime during the late 1800s. He spots an opponent palming an ace and shoots the opponent dead. At this point, the Celestial Toymaker appears and invites Lefevre to play against him. Agreeing, Lefevre is instantly transported to the Toymaker’s domain. As he enters, he passes life-size statues of people. One I particularly remember noticing, on the story’s last page, was of an American second world war soldier which would have been about half a century in Lefevre’s future.

They start to play cards and initially, Lefevre does well, but when his luck changes, Lefevre tries to cheat. When the Toymaker cheats back, saying that he believed Lefevre had invented a new rule, Lefevre tries to shoot the Toymaker. This is the Toymaker’s domain where he even controls gravity and the bullet lands harmlessly on the card table.

“The game is forfeit, and you have to pay!” cries the Toymaker and Lefevre is turned into a statue in which he is to become one of the Toymaker’s toys.

Presently, a Roman centurion enters the domain, also having taken up a challenge from the Toymaker, and he passes Lefevre’s ‘statue’.

I was about 15 when I read that.

From that story, I didn’t get the sense of evil about the Toymaker; as far as I was concerned, it was a morality tale about honesty. Lefevre is a nasty piece of work who kills in cold blood over a game! I presumed that all the other “toys” present had also been wrong-uns who ended up being turned to stone as they fell into their nefarious ways during their gamble. And did the Toymaker choose these people for that reason?

On the face of it, The Greatest Gamble is a morality tale: a cheat and a murderer gets his comeuppance. But the tale itself relies on the reader’s prior knowledge of the Celestial Toymaker. I didn’t have that prior knowledge when reading this tale for the first time and this is only four pages long; the magazine’s secondary strip doesn’t have the time for any kind of resume.

As a result, what I perceived was that the Toymaker was bored and lonely; a celestial being plundering time and space for people to gamble against simply to relieve the monotony. But there was something more than that. The Toymaker, on this occasion, comes across as some kind of avenging angel; to dish out a punishment for the evil that men do.

Of course, I subsequently got to know the original television story better and revisiting The Greatest Gamble today there were clues that the gambling is the point. Had Lefevre played fairly and won, he would have been sent back to the casino on the Mississippi steamer, with his winnings, despite having just committed murder. However, should he have lost, even fairly, he certainly would have suffered the dreadful fate to become one of the Toymaker’s playthings. After all, the Toymaker says to Lefevre that he has no use for money… what would be the Toymaker’s winnings otherwise?

However, in this story the Roman centurion is brought into the tale as another gambler. This gives the impression that the Toymaker is only looking for gamblers to play against. This was something else that familiarity with the original television story put right for me: the situation was even simpler; it was losing or winning a game – any game – as was the case when the First Doctor was presented with the Trilogic puzzle.

One last thing occurred to me back in 1981, when I first read The Greatest Gamble: were the gamblers who turned to stone killed or had they been placed in some statuesque eternal torment rather like Borusa in The Five Doctors?

And finally, a mention regarding the artist, Mick McMahon. McMahon had such a distinctive style and he was probably most famous for his work on Judge Dredd. For me, what springs to mind is his characters always have exaggerated shoes and hands, but the art itself has a gritty cartoon feel. I am lucky enough to have an original page from his work on Judge Dredd: The Cursed Earth… and, in a strange coincidence to the Toymaker story, it’s the page when Dredd discovers the mafia-style judges in Las Vegas.

Don’t gamble, kids!

[Editor’s Note: I would just like to extend my congratulations to Colin and his new wife, Karen, on their wedding day. I’m so happy for you both. Colin is a fantastic chap, and I know you’ll be very happy together. Please join me, DWC readers, in wishing them all the very best for the future!]